Fatigue and Hearing Loss

September 6, 2023 Leave a comment

What is fatigue?

Fatigue is a term used to describe tiredness, typically over a long period of time. It can be used to refer to physical or mental fatigue, a combination of both, or a symptom. Broadly, it can be used to refer to feelings, or behaviorally, as various measures of physical or mental performance [1].

How is hearing loss related to fatigue?

There is evidence to suggest that people with hearing loss are at a higher risk of experiencing fatigue than those who have normal hearing, due to increased listening effort [1, 2, 3]. A recent cross-sectional study examining the association between hearing loss and self-reported fatigue in 3,031 participants in the US (as part of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) showed that those with hearing loss were more likely to report fatigue for more than half the days and nearly every day than not having fatigue even when other factors such as age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, smoking, drinking, noise exposure, and body mass index was accounted for [4]. The study reports the relative risk ratio (RRR), which is the probability of the event occurring in the group with exposure (in this case hearing loss) versus those without. A relative risk ratio of greater than 1 means that the event is more likely to occur if there was exposure. Every 10-dB HL–worse of audiometric hearing was associated with a higher likelihood of reporting fatigue for nearly every day (RRR = 1.24; 95% CI, 1.04-1.47) but not for more than half the days [4].

What implications does fatigue have for those with hearing loss?

Fatigue, particularly chronic fatigue can result in:

- reduced quality of life

- deficits in cognitive processing (maintaining attention, thinking quickly, clearly, or efficiently)

- reduced workplace productivity and safety [1]

Do hearing aids help?

There is not definitive evidence yet. The quality of evidence available from a systematic review to answer the questions of whether hearing loss has an effect on fatigue and whether hearing device fitting has an effect on fatigue is “very low” [5]. Having said that the review did highlight support for these questions.

There is some support that hearing loss increases fatigue; the “very low” risk categorization is due to lack of homogeneity among studies, and that there haven’t been any randomized clinical trials conducted thus far. Evidence from self-report measures did not support the hypothesis that hearing aids reduced fatigue in full, although the evidence was more promising for cochlear implants than hearing aids. There was a positive result from one study that used behavioral measures, suggesting that more studies with validated and consistent fatigue measures are needed to examine this hypothesis cogently.

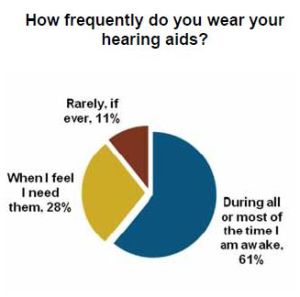

A longitudinal study by the same group looked at the effect of hearing aids before fitting, at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months post-fitting and found that hearing aid fitting significantly reduced listening (-related) fatigue but not general fatigue. Social activity and participation levels also were shown to be increased in the hearing aid group relative to the control group [6].

Given the role of motivation in the framework of listening effort, it is possible that motivation may directly or indirectly contribute to listening fatigue [3]. The interplay between fatigue and motivation to wear hearing aids has yet to be examined.

What to do about fatigue?

The following practices help with general fatigue, and likely listening fatigue:

- healthy diet and exercise

- good and consistent sleep schedule

- lower stress

- socializing that gives enjoyment

If you have hearing loss and own hearing aids, wear that hearing aid you purchased…and do things you love.

References

- Hornsby, Benjamin W. Y., Graham Naylor, and Fred H. Bess. “A Taxonomy of Fatigue Concepts and Their Relation to Hearing Loss.” Ear & Hearing 37, no. 1 (July 2016): 136S-144S. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000289.

- Hornsby, B. W. (2013). The effects of hearing aid use on listening effort and mental fatigue associated with sustained speech processing demands. Ear Hear, 34, 523–534.

- Pichora-Fuller, Kathleen, M., Sophia E. Kramer, Mark A. Eckert, Brent Edwards, Benjamin W. Y. Hornsby, Larry E. Humes, and et al. (2016). “Hearing Impairment and Cognitive Energy: The Framework for Understanding Effortful Listening (FUEL).” Ear and Hearing 37, no. 1: 5S-27S.

- Jiang, K., Spira, A.P., Lin, F.R., Deal, J. and Reed, N. S. (2023). Hearing Loss and Fatigue in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. JAMA, 149, 8, 758-760

- Holman, J.A., Drummond, A., and Naylor, G. (2021). The Effect of Hearing Loss and Hearing Device Fitting on Fatigue in Adults: A Systematic Review. Ear andHearing, 42 (1), 1-11.

- Holman, J. A., Drummond, A., and Naylor, G. (2021). Hearing aids reduce daily-life fatigue and increase social activity: a longitudinal study. Trends in Hearing, 25, 23312165211052786.

Hiking in the Smokies, I was on the

Hiking in the Smokies, I was on the